Manchuria Literarian

“A literarian is someone who loves literature so much that he or she wants to share it with as many people as possible...” (A Way with Words)

Hello and welcome! 大家好, 안녕하세요! I am a literary scholar in Asian studies and I created this site is to share the history, literature, and culture of northeast China. My academic research focuses on the early twentieth century, in particular the period from 1931-1945, when the Japanese empire created a state called Manchukuo. In the blog, I share conference talks and short articles from my PhD research on the interactions between Chinese and Korean writers in Manchukuo. My personal interests, however, extend beyond the Manchukuo period and into the twenty-first century. Around the site you'll also find current news and information about "northeast literature" (东北文学), including works in Korean by Korean-Chinese (조선족) writers. Finally, I also share some of the creative projects and translations I've been working on, as well as my professional journey in academia.

With the curiosity of a beginner

Imagine exploring your research terrain as a beginner, with all the curiosity, liveliness, and sensory awareness […] of an animal, a child, or just someone young at heart. What catches your eye, or your nose? What delights you? When you look at your project through fresh eyes, what can you see that you couldn’t before? (From #AcWriMoments Day 3)

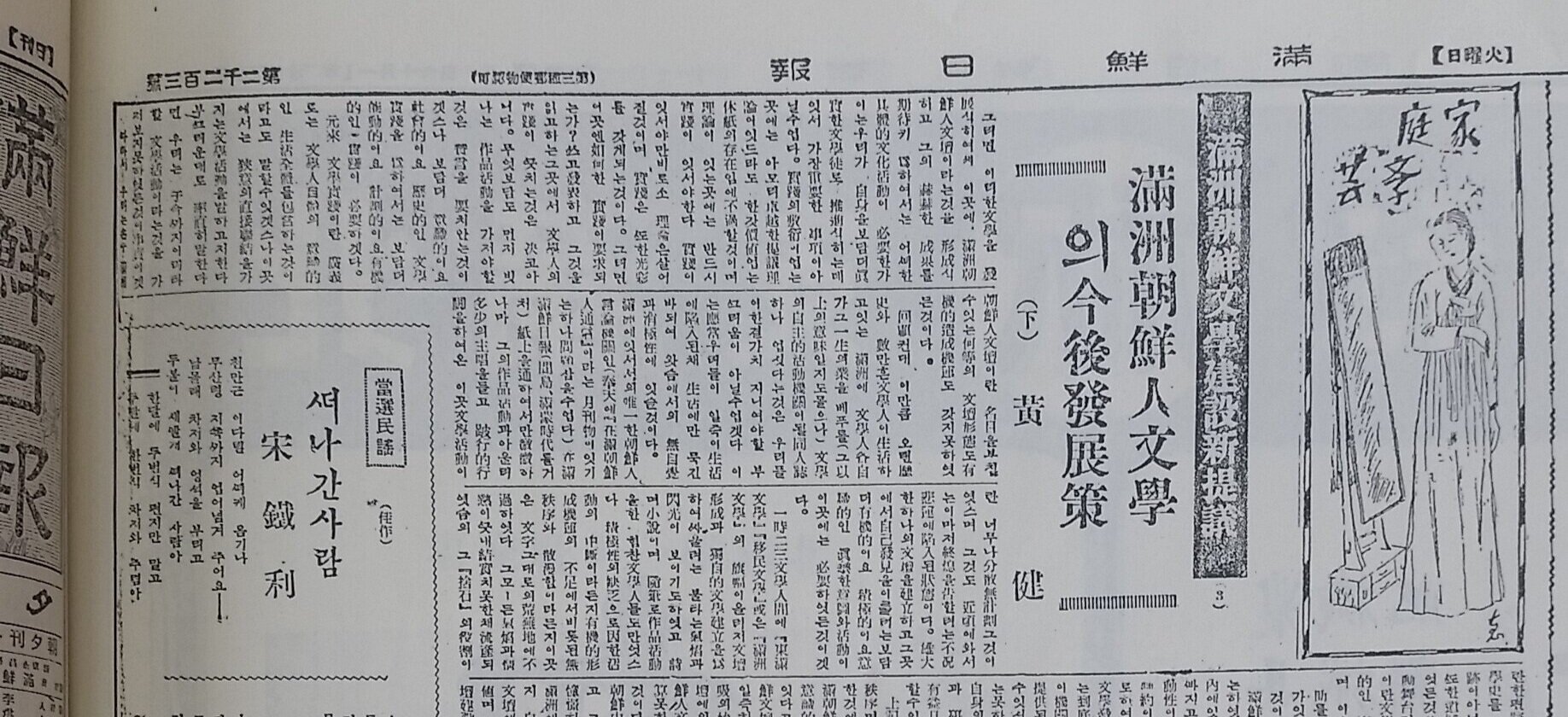

I still remember what it felt like to ‘find’ the army songs. The singer in me couldn’t help but sight-sing the scores provided in the tomes I found in the library. Or that one time I found the Manchukuo radio program schedule in a scanned copy of the Manson ilbo (the only Korean-language newspaper in Manchukuo after 1937). I imagined the type of person who might have had access to a radio: them turning it on, tuning to the right station, listening to a radio drama or music before bed at night. Those were exciting finds.

I’m getting caught between thinking through this prompt as a student versus as a researcher. My primary texts are so well hidden that a person would have to have a certain base of knowledge first and be extra curious in order to find them. Is that not the way with archival research, thought? I imagine presenting the texts to a student who doesn’t have to go find them, yet does have to read and make sense of them. I imagine my student M, for example, who is interested in humor in literature, reading Imamura Eiji’s ‘The Crossings’ or An Sugil’s ‘Kitchen Girl’ comparing the ways these stories use humor and to what end. That would be a very new experience for her, and I wonder if she would enjoy it.

I wonder what M would learn about Manchuria by doing such a project. I had the fortune of studying about a place where I had lived. When I read something about the big avenues of Changchun in a text, I remembered walking down Renmin dajie or Ziyou dalu (not that they were called by such names in the 1940s). I could still feel the big trees and the June pollen. When the characters in ‘The Crossings’ started on their journey, I could recall the flat terrain and the late summer monsoons. And, oh, the winters! When the soldiers, be they Chinese or Korean, sang about ‘warring in the snow’, I could hear the quiet crunch of a fresh fall underfoot, the drooping branches of the pine trees laden with the white fluff. M wouldn’t have had that first-hand experience. On top of that, she would read those works as ‘Chinese’ by virtue of them being produced in the wider geographical area of China. Would she be able to sense the nuances of the place? And so what if she couldn’t? How important is that for undertaking research of literature from Manchuria/Manchukuo?

By pondering on this prompt, what can I see that I couldn’t see before? Looking at the Manchukuo era from the perspective of humor would be an interesting study. Comparing comics in the newspapers there to newspapers in the south might be informative. Did writers in Manchukuo use humor differently or for a different purpose than other Chinese writers? Well, both of the stories I cited above were actually written by Koreans (even though I have translated them from Chinese translations), so would it be more suitable to compare them to Korean writers? Thinking of other texts I have studied, such as Wai Wen’s Chinese translation of the stage play The Tale of Chunhyang and An Xi’s radio play Zhu Maichen, it’s like there is a boiling point where the humor turns into rage…which makes me wonder if that tactic works because these are scripts instead of prose?

As an addendum to this #AcWriMoments prompt from last year, this year’s initiative Tarot for Scholars, starts very fittingly with the Fool card. I won’t go into the symbolism and meaning of the card (for now), but I will say this: I would be a fool not to take on the research project I described above!

SACRED ambitions

Wow, it has been a long time since I’ve updated the website and written a blog post. I am restarting now with help, thanks to an initiative begun by Margy Thomas and Helen Sword, which they have called #AcWriMoments. It is 30 days worth of prompts about one’s academic writing and thinking. (Technically, this initiative fell in line with #NaNoWriMo and #AcWriMo last November, but I purposely only drafted my prompts to work on later; hence, my publishing them now). Since I’ve been facing a crisis of purpose lately with regard to writing and academia, I thought it might be good for me to take a moment (!) to reflect.

Honestly, I didn’t fully grasp the prompt on Day 1. Rereading it now a few months later, I understand better the aim: finding the will to carry on by finding inspiration, even guidance, in moments great or small. They distilled their idea into the acronym SACRED:

Strategic moments

Artisanal moments

Creative moments

Reflective moments

Embodied moments

Delicious moments

It’s not often that academic writing is treated as something ‘creative,’ ‘artisanal,’ or ‘delicious,’ let alone SACRED. Yet now that I think about it, I became attracted to academic texts partly because of the lofty, refined style. I love it when a scholar manages to express an argument eloquently and rationally. To be able to take pride in writing like that has been one of my longest-standing dreams. And if I’m really honest, I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to do it. Maybe I don’t even want to anymore. I don’t know whether it’s burn-out speaking, the pressure of academia, or the fallout from the pandemic, but writing feels more and more like a luxury.

I can see that SACRED is meant to be a tool I can fall back on when ambitions begin to fade and the mundane starts to clutter the mind. A part of me is thanking myself for participating in #AcWriMoments all those months ago for what it’s giving me today: a moment to reflect and embody my hopes for the future. Especially now that I have decided to leave Malta (a topic for another post), and am facing a move back to my home country as well as unemployment, this question of what writing means to me is always somewhere on my mind. I’m glad to be publishing this post. That’s a decent step forward, right?

Presentations

A gallery of talks from conferences, seminars, and other public engagements